GIS Analysis: Amphitheater

|

The remains

of a large amphitheater are visible approximately 1000 meters

to the northeast of the forum. A large (78.6 X 51.6 m.) elliptical

depression in the modern fields mark the remains of the ancient

facility (figure 1). The floor of the structure, arena,

and the stone seats were cut out of the bedrock and it is likely

that the original superstructure was constructed of wood. The

location of the amphitheater, in the northeast corner of the

"drawing board plan" of the Caesarean colony of 44 B.C., would

be have been in keeping with the design of Roman cities, where

amphitheaters were commonly situated immediately inside or outside

the limits of the city. A roadway, cardo XXVII east,

approaches the amphitheater from the south and served as the

principal access to the structure (figure 2). The point at which

the roadway met the amphitheater was likely to have been the

Porta Triumphalis that would have served as the entrance

to the arena for the gladiators and other performers. At the

north end of the amphitheater is a rock cut entrance that likely

would have been the Porta Libitinensis, the exit for

gladiators and animals. One of the only plans produced of the

amphitheater in Corinth comes from Abel Blouet, a French scholar,

who published the plan to the right in the 1830's. The plan

clearly illustrates the elliptical shape and the seating plan

of the amphitheater (figure 3).

The amphitheater was the place

where gladiatorial games, munera gladiatoria, were held.

Gladiators were usually prisoners of war or condemned criminals

and were known to be of four types: the murmillo who

carried a short sword, a rectangular shield and a helmet with

a fish crest; the Samnite who had a short sword, oblong

shield, greaves and visored helmet; the retiarius who

fought with a trident and a net and the Thraex who carried

a round shield and a curved sword. Other events that likely

occurred in the amphitheater included wild animal hunts, venationes.

It is interesting to note that

during the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D., both the odeum and the

theater near the forum of Roman Corinth were readied for gladiatorial

contests. In both cases, the orchestras of the facilities were

converted for use. In the theater, wall paintings have been

discovered that depict gladiatorial contests and wild beast

hunts. Figures 4 and 5 are frescos taken from the theater in

Corinth. They depict scenes of gladiators fighting the types

of wild beasts that were imported into Corinth for the gladiatorial

games. Figure 4 depicts the gladiator highlighted in blue and

a lion highlighted in yellow. Figure 5 depicts two gladiators

highlighted in blue fighting a bull, highlighted in yellow.

These photographs illustrate the

amphitheater in the early twentieth century. Figure 6 shows

the northern end of the amphitheater including the subterranean

passage. Figure 7 shows the amphitheater floor and aspects of

the seats in the eastern section. Figure 8 shows the arena floor,

looking southeast.

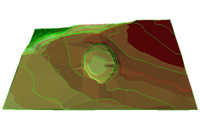

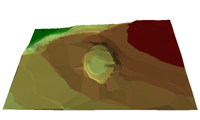

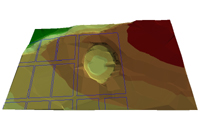

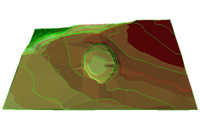

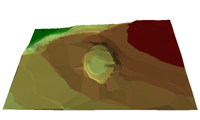

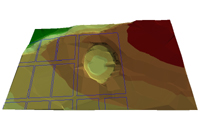

The illustrations

below are 3D models of the amphitheater region that where made

by digitizing 1:2000 topographic maps. After digitization in

AutoCAD, the contour lines were assigned their appropriate Z

value. The 3D contour lines were then imported into ArcView

and a either a wire-frame model or a Triangulated Irregular

Network (TIN) was rendered. The final stage before analysis

was to drape ground level or aerial photograph over this 3D

model for further ground cover relief or enhanced visualization.

Figure 9 illustrates

the 3D contour lines combined with a TIN skin. Figure 10 illustrates

a 3D model with various shades of color denoting elevation change.

Figure 11 illustrates the "drawing board plan" of the Caesarean

colony of 44 B.C. draped on top of the 3D model.

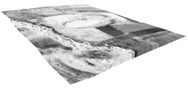

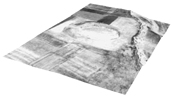

The figures below (figure 12,

figure 13, and figure 14) demonstrate how this type of computerized

data can be used for interpretative purposes. These figures

show a low level aerial photograph draped on top of the initial

3D model. Remote sensing, slope analysis and historic view sheds

are examples of useful research that can be conducted with this

type of 3D data.

|

Figure 1

Click on the

images to enlarge.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

|

Figures 9, 10, 11

(above); Figures 12, 13, 14 (below)

Testimonia: Dio

Chrysostom, 31.121 (translation adapted from the Loeb Classical Library)

For instance, in regard

to the gladiatorial shows the Athenians have so actively emulated

the Corinthians or really have surpassed them and all others in

their mad infatuation, that whereas the Corinthians watch these

combats outside the city in a gully, a place that can accommodate

a crowd, but otherwise is dirty and such that no one would even

bury a freeborn citizen there...

Media:

Listen

to a Real Audio broadcast from Philadelphia's National Public

Radio Station WHYY.

The show "Radio Times" features a discussion of Roman

gladiators. This radio broadcast features Professor Brent Shaw, Department

of Classical Studies, University of Pennsylvania. This show was aired

on May 6, 2000. Fast forward to the 1.05 hour mark to hear the discussion

on gladiators. Click on the Real logo to download and install the

free plug-in. Listen

to a Real Audio broadcast from Philadelphia's National Public

Radio Station WHYY.

The show "Radio Times" features a discussion of Roman

gladiators. This radio broadcast features Professor Brent Shaw, Department

of Classical Studies, University of Pennsylvania. This show was aired

on May 6, 2000. Fast forward to the 1.05 hour mark to hear the discussion

on gladiators. Click on the Real logo to download and install the

free plug-in.

Bibliography:

H.N. Fowler and R. Stillwell,

Corinth I, Introduction, Topography, Architecture, American

School of Classical Studies at Athens, Cambridge, Mass. 1941, pp.

89-91; figs. 54-56.

K. Welch, "Negotiating

Roman Spectacle Architecture in the Greek World: Athens and Corinth,"

in The Art of Ancient Spectacle, B. Bergmann and C. Kondoleon,

eds, Yale University Press, 2000, pp. 125-145.

For Further Reading:

T. Wiedemann, Emperors

and Gladiators, Routledge, London, 1995.

Figure Credits:

- Hellenic Air Force, 1963, Courtesy

Corinth Excavations, American School of Classical Studies.

- Corinth Computer Project, 2000

.

- Abel Blouet, Expédition Scientifique

de Morée, Paris, 1831-1838, 3, pl. 77, fig. II.

-

Richard Stillwell,

Corinth II, The Theater, ASCSA, Princeton, 1952, fig.

77, p. 89.

- ibid. fig. 80, p. 91.

- Corinth I, Introduction, Topography,

Architecture, ASCSA, Harvard

University Press, 1932, fig. 56, p. 90.

- ibid.

fig. 55, p. 89.

- ibid. fig. 54, p. 88.9-14

- Corinth Computer Project, 2000.

- Corinth Computer Project, 2000.

- Corinth Computer Project, 2000.

- Corinth Computer Project, 2000.

- Corinth Computer Project, 2000.

- Corinth Computer Project, 2000.

|