Competing against ancient myths

Scholars challenge long-held beliefs of early Olympics

08/08/04

By Joseph B. Verrengia

Associated Press

It was like the Super Bowl, Woodstock, Mardi Gras, a holy

pilgrimage and Chippendale dancers all rolled into one.

|

Greek actresses dressed as high priestesses

take part in a dress rehearsal March 24 at Ancient

Olympia on the eve of the official flamelighting

ceremony for the Olympic Games. In ancient time,

contestants roasted meat and offereings in the sacred

flame. Photo by AP |

The setting for the earliest Olympic Games some 3,000 years

ago was a sanctuary of soaring marble temples and a foul,

drunken shantytown plagued by water shortages, campfire smoke

and sewage. The athletes, glistening from olive oil, competed

naked. Gymnasiums were restricted to keep the sex trade from

overrunning events on the field.

With the 2004 Summer Games set to begin this week in

Athens, archaeologists and scholars are demythologizing and

viewing the original Olympics as they really happened.

Contrary to the modern stereotype, the Games weren't

tightly scripted Homeric epics in which warriors dropped their

weapons every four years to honor the twin virtues of amateur

sport and brotherhood.

While the Olympics' 3,000-year history is dotted with the

heroic champions like the wrestler Arrhichion who fought to

the death, researchers say they also were plagued by cheating,

scandal, gambling and outsized egos.

"The ancient Greeks were not as idealistic as we represent

them to be," says David Gilman Romano of the University of

Pennsylvania Museum and director of a new excavation at Mount

Lykaion, 17 miles from ancient Olympia. "They had many of the

same problems we have today."

The ancient Games were held in a remote valley.

Forty-thousand spectators crowded a hillside above a sacred

precinct containing some of the greatest temples in the

empire. Sport, they believed, was a high tribute to the gods,

who favored the athletes who won.

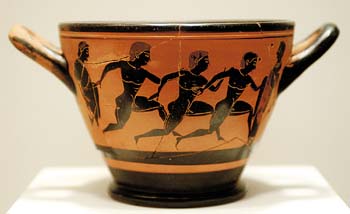

|

A

painted vessel showing runners and dated 540 B.C. is on

display at an exhibition at the National Archaelogical

Museum in Athens. The exhibition "Agon" -- the Greek

word for contest -- will run through Oct. 31. Photo by

AP |

Before the Games, athletes pledged their piety as they were

paraded past a row of statues of gods and former champions

that were paid for from the fines of disgraced cheaters. At

the feet of a 40-foot statue of Zeus -- one of the seven

wonders of the ancient world -- they sacrificed oxen and boar

and roasted hunks of the flesh in a sacred flame.

Then the Games would begin, lasting five days. The athletes

would consult fortunetellers and magicians for victory charms

and potions -- the ancient precursors to steroids, classics

experts say -- as well as curses on their opponents to fail.

The first recorded incident of actual cheating occurred in

388 B.C. when the boxer Eupolus of Thessaly bribed three

opponents to take a dive.

Others were induced to swap allegiance, often at the risk

of exile from their homelands. The city-state of Syracuse was

as notorious as New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner in

its quest for free agents that would bring religious favor and

glory.

When Syracuse induced sprint champion Astylos to quit

Kroton in southern Italy, fans in his hometown tore down his

statue and turned his house into a prison.

Olympic corruption peaked under Roman influence; in A.D.

67, emperor Nero bribed the judges to include poetry reading

as an event. They also declared him the chariot champion,

overlooking that he fell out and never finished the race.

For the fractious city-states of the empire, the Games held

every four years offered a slightly less violent respite from

their near-constant state of war. Athletes and spectators from

all parts of the realm were promised safe passage to and from

the neutral site.

The experience of competing against -- or cheering

alongside -- battlefield rivals brought out the best and worst

in human nature, especially when immortality was at stake.

|

The

arm of a boxer from a statue from the late 2nd century

B.C. is part of the exhibition at the National

Archaelogical Museum in Athens. Photo by AP

|

"Sport was sort of like war," says University of

Texas-Arlington classical history scholar Donald G. Kyle.

"Participation wasn't enough. They wanted to win so badly, and

they feared losing so much. What we're willing to do to win

says an awful lot about our societies."

Archaeologists have uncovered some evidence of the

complexity of the ancient Games in excavations at Olympia and

other sites that hosted preliminary contests, including discus

fragments, javelin points and metal objects that could be

prizes or religious votives.

Greek art adds rich visual details to the historical

record, with paintings on vases, urns and other fine pottery

the most important source. They depict disfigured boxers with

bloody noses and sprinters thundering down the track, elbows

flying. Judges flogged the athletes for transgressions ranging

from false starts on the track to eye gouging in the ring.

Literary sources offer still more details, from florid

victory odes to inscriptions on statue pedestals.

Experts differ on the number of Olympic events. Was it 14

or 18? The mule cart race was held for just 56 years in the

5th century B.C. And, should the competition for heralds and

trumpeters be counted? Regardless, the Games were considerably

smaller than the 300 rounds of competition staged now with

10,500 athletes from 202 nations.

A few events have persisted over the millennia, like the

discus, javelin, running, wrestling and boxing -- although the

ancient versions often had different rules. Other events

vanished with the empire, like the full-armored sprint and the

pankration -- which resembled a bar fight that allowed

finger-breaking and genital punching.

Only first-place winners were symbolically crowned with

laurel wreaths, but the rewards hardly ended there. Today's

concept of amateur status would've been foreign in ancient

Greece.

These champions were the Michael Jordans of their day,

showered with fame and prizes, including huge annual stipends

and prized commodities like the best olive oil, free meal and

theater seats, hometown parades, statues and sex partners.

The shamed losers, according to the poet Pindar, would

"slink through the back alleys to their mothers."

Excavation of athletic facilities show differences with

modern stadiums, too. Instead of today's oval tracks, the

straight track, or stade, at Olympia is 198.28 meters. Runners

raced its length and rounded a post at the far end. In some

events, they might do this 15 times.

The first Olympic champion was a cook named Koroibos who

ran in 776 B.C. Perhaps the greatest runner was Leonidas of

Rhodes, who won all three footrace events in four consecutive

Olympics beginning in 164 B.C.

The balbis, or starting line, in Greek tracks usually was

made of stone blocks set in the ground; runners would wedge

their toes into parallel grooves carved in the stone, leaning

forward.

Seventy miles from Athens at Nemea, reconstructions by

University of California-Berkeley archaeologist Steven G.

Miller suggest races were controlled by a judge standing in a

manhole behind -- and below -- the poised runners. He pulled

tight on ropes that kept a hinged gate upright. When the

trumpet blared, the judge dropped the ropes, the gates fell

and the runners took off.

In later centuries, the whole system -- called a hysplex --

became more automated by pulleys and a spring.

Also at Nemea, Miller has excavated the locker room where

athletes slathered themselves with oil, and the vaulted tunnel

that leads to the track. Its walls are still bear their

graffiti, some of it reflecting the homoerotic nature of the

ancient games.

Miller cites an example in which one athlete praised the

physique of another, writing, "AKROTATOS KALOS" or "Akrotatos

is beautiful." Another athlete wrote "TOU GRACANTOS" or "to

the guy who wrote it!"

That the ancient Games were a very human spectacle of

blood, sweat, sex, money and stench doesn't diminish their

historical and cultural importance, experts say.

Nor should it tarnish the athletes' achievements.

That becomes clear if you were to stand at the end of a

hot, long ancient track -- fully clothed, presumably -- and

pretend that your name is Leonidas, ready to run.

"It really is a thrill," Miller says, "to be a part of

ancient Greece, if only for a few minutes as you come out of

the locker room, through the tunnel, to put your toes in the

ancient starting grooves."

|